Lame Excuse: Rubio Cuts Off Funding to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA)

On March 15, President Biden signed a massive $1.5 trillion omnibus spending bill (H.R. 2471) that will fund federal agencies and programs through the end of fiscal year (FY) 2022 on September 30. The long delayed, 2741-page spending package fails to include any of the significant advances for sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) passed by the full House and proposed by the Senate Democratic majority on the appropriations committee, specifically increased funding for international family planning and reproductive health (FP/RH) programs and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) or the permanent repeal of the Global Gag Rule (GGR). Instead, due to the unrelenting demands of anti-SRHR members of Congress on the Republican side of the aisle, the bill defaults to the previous year’s funding levels and policy, essentially retaining the status quo that has persisted on these issues for more than a decade.

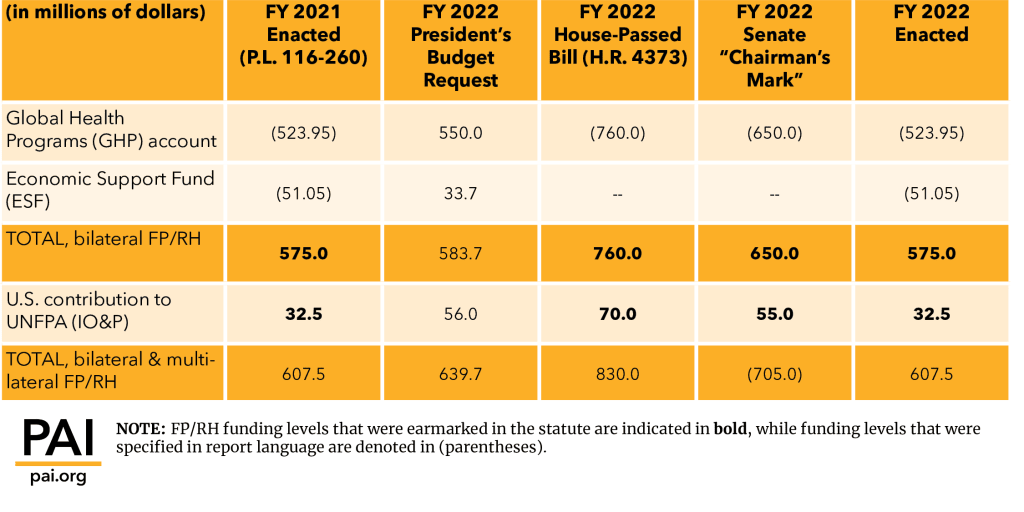

The final spending package continues to fund bilateral international FP/RH at $575 million, with an additional $32.5 million for UNFPA, totaling $607.5 million overall. This amount has remained consistent for 12 years, despite the need for increased investments to adequately address the unmet need for modern contraception and other reproductive health services, as well as to offset the effects of inflation.

In addition, the bill fails to include important policy changes to improve the efficacy and efficiency of U.S. investment in international FP/RH programs. Most notably, permanent repeal of the GGR was left out. Included for the first time in both the House and Senate bills in FY 2022, this policy change should have been considered an issue that did not need to be negotiated as the chambers came together to form an agreement on a final spending package. Without this change, global health organizations around the world remain in a state of uncertainty, knowing that this harmful policy could come back as soon as a future U.S. president who is hostile to SRHR takes office.

As predicted, the longer the appropriations process dragged on into the fiscal year, the greater the likelihood of a disappointing outcome for SRHR advocates. As a result of the five-month delay, there were two possible appropriations outcomes: either a year-long continuing resolution (CR) — reflecting a continuation of outdated and distorted Trump-Pence administration funding and program priorities — or passage of a severely watered-down omnibus bill in February or March. The former scenario was avoided, but Congress defaulted to the latter.

Senate Republican leadership insisted on parity in funding increases between defense and nondefense discretionary programs and refused to accept any changes in policy “riders” across a broad range of issue areas. The seeming willingness of a significant proportion of their party caucus to shut down the government or to accept a year-long CR that would undermine their own stated objective to increase defense spending, proved to be a powerful — albeit reckless and irresponsible — bargaining position.

That does not absolve Democrats of responsibility for the outcome. With Republicans wielding the 60-vote threshold necessary to approve bills in the Senate these days as a cudgel, at some point, a deal was struck, and a concession on policy “riders” in exchange for other Democratic priorities was made. In the past, when there were good-faith negotiations between appropriators, international family planning funding and policy questions were among the last issues to be resolved before omnibus spending packages were finalized. It is unclear if there was ever a substantive discussion this year, contrary to well-established committee norms and practice, and when Democrats made the decision to relent on “riders.”

There will be time enough for post-mortems in the coming days, but what is most important to understand in the present is what happened — and perhaps less about how or why it happened.

Global Gag Rule

With both the House-passed bill and the Senate version containing a permanent legislative repeal of the GGR, the stage was set for a breakthrough to end the constant back and forth of this destructive executive branch policy between Republican and Democratic presidents once and for all. But it was not to be.

Based on provisions of the Global Health, Empowerment and Rights (Global HER) Act (H.R. 556 and S. 142), the language included in both the House and Senate bills would have ensured that non-U.S. nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) are not prohibited from receiving U.S. assistance based on their provision of abortion services, counseling or referrals with non-U.S. funds if permitted in the country in which they operate and in the United States. Furthermore, the language would ensure that non-U.S. NGOs are treated fairly and afforded the ability to engage in permissible advocacy and lobbying activities on abortion with non-U.S. funding. This language would amend the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, the permanent foreign assistance authorizing statute, and would prevent a future president who is hostile to SRHR from unilaterally imposing the GGR through executive action. While President Biden revoked the Trump-Pence administration’s dramatically expanded version of the GGR, enactment of this legislative change would have ensured that the United States can provide funding for and build sustainable partnerships with locally led NGOs and make long-term progress on a range of critical health issues.

With permanent GGR repeal included in both the House-passed bill and its Senate companion, this should have been “non-conference-able” — not a subject for the negotiation between the two chambers to resolve differences between their respective versions. But as feared, the Republican leadership labeled the GGR repeal amendment a “poison pill,” threatening Senate passage, and were successful in removing it from the final spending package.

Funding

On international FP/RH funding, the omnibus bill stipulates that “not less than” $575 million “should” be provided to bilateral FP/RH programs, the bulk of which — $524 million — is allocated within the Global Health Programs (GHP) account managed jointly by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Office of Population and Reproductive Health and USAID country missions in the field. The remainder is allocated from within the Economic Support Fund (ESF), which has been used in the past to finance FP/RH activities in a small number of strategically important countries.

While both the House and Senate versions of the bill proposed that no portion of the bilateral FP/RH funding amount be derived from ESF and allocating all funding through the GHP, a departure from past practice which would have allowed USAID greater flexibility in choosing which countries wherein these funds could be utilized, the omnibus explanatory statement contains a line-item budget of $51 million from ESF for FP/RH. It is apparent that congressional appropriators resorted to the perennial past practice of using ESF to bolster the FP/RH level in the face of competing pressures for scarce resources available under the overall funding allocation for GHP programs.

The U.S. contribution to UNFPA is earmarked at $32.5 million from within the International Organizations and Programs (IO&P) account that includes all the voluntary contributions made by the United States to U.N. programs and agencies.

Together, combined bilateral and multilateral FP/RH funding totals $607.5 million, leaving funding stagnant for the last 12 fiscal years at just over $600 million annually. Over those dozen years, adjusting for inflation, the purchasing power of the appropriated FP/RH funds has decreased by $138 million in constant FY 2011 dollars. Conversely, the FY 2011 appropriated amount would have the purchasing power of $759 million today. The high-water mark for international FP/RH funding, enacted by Congress just prior to the landmark 1994 International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo, would have the equivalent purchasing power today of $1.027 billion. While these adjustments for the effect of inflation are stark, the calculation does not reflect the growth in the population of reproductive age over those years.

Several weeks ago, advocates began to hear that Republican appropriators had started to refer to any FP/RH funding increase as a “poison pill,” a term typically reserved for unacceptable policy provisions being attached to a funding bill. Historically, maybe in the too far distant past, FP/RH program funding increases were typically the consolation prize awarded when congressional appropriations champions were unable to deliver pro-SRHR policy wins. But even reaching an agreement to fund FP/RH at the level at which it has been stuck for the last 12 years — while permanent GGR repeal was being stripped out — appears to have been a battle in and of itself. Noteworthy perhaps is that House Appropriations Committee Chair Rosa DeLauro’s summary of the State Department and foreign operation title of the omnibus lists as a highlight of the agreement that it “supports women’s health globally by preserving funding” for bilateral and multilateral FP/RH programs. This might be reading far too much into a word choice, but “preserving”?

The flat funding level for FP/RH was probably also the result of the influence of other external factors unrelated to the unique challenges posed by its association with abortion politics. The low overall funding allocation for international affairs programs — the smallest increase at only 1.1% above the current-enacted level among the 12 subcommittees while nondefense discretionary programs of which it is a part received a 6.7% bump up overall — put tremendous pressure on funding for global health programs in general. Combined with the approval of a half-billion dollar increase to $700 million for global health security, little room was left for increases for most other global health sectors, including FP/RH. The apparent evaporation this year of the bipartisan consensus on the importance of robust investments in foreign assistance in Congress and the seeming lack of prioritization by the White House is troubling.

UNFPA

The omnibus earmarks a U.S. voluntary contribution to UNFPA of $32.5 million out of the IO&P account, an amount identical to the contribution level enacted for the last six fiscal years and just slightly less than the amounts appropriated for the preceding four years. More significantly, the final contribution in the omnibus is $37.5 million less than amount earmarked in the House bill and $22.5 million less than the amount earmarked by the Senate.

The omnibus reiterates all the long-standing boilerplate restrictions requiring UNFPA to maintain U.S. funds in a segregated account — none of which may be spent in China, nor fund abortions. In addition, the omnibus retains the dollar-for-dollar reduction in the U.S. contribution provided to UNFPA by the amount UNFPA spends in China each year, which amounted to a reduction of $1.7 million in the FY 2021 contribution. The requirement that any funding withheld from UNFPA due to the “operation of any provision of law” is to be reprogrammed to USAID for family planning, maternal and reproductive health programs also remain.

One other significant proposed policy change that was left out of the omnibus was a modification of the Kemp-Kasten amendment, which prohibits furnishing U.S. foreign assistance to any organization that “supports or participates in the management of a program of coercive abortion or involuntary sterilization.” This is the legal provision invoked by all Republican presidents since 1985 to bar funding to UNFPA. Both the Senate and the House bills inserted the adjective “directly” before the phrase “supports or participates in the management” of programs engaged in coercive practices, tightening the room for willful misinterpretation of the text of the amendment by future Republican presidents and political appointees hostile to UNFPA. That proposed change was also scuttled.

During FY 2021, UNFPA has received additional humanitarian and refugee assistance from other foreign assistance accounts for critical reproductive and maternal health and gender-based violence prevention activities for the agency’s response to the Rohingya refugee crisis and for addressing humanitarian needs in the Tigray Region, Afghanistan, Sudan and Yemen. Presumably, U.S. financial support for UNFPA’s ongoing presence and support to Ukraine, where more than 4,300 births have occurred since the start of war and an additional 80,000 women are expected to give birth in next three months, should be forthcoming along with additional resources for UNICEF and the World Health Organization. The omnibus includes $13.6 billion in emergency funding for Ukraine, some of which is designated for humanitarian purposes.

Global Health Sector Equity

Although the highest policy priority for FP/RH advocates in the omnibus negotiations was enactment of the permanent legislative repeal of the GGR, the recent “coup” in Burkina Faso provides a timely example of why a technical language change to include FP/RH programs under a broad global health exemption from country aid prohibitions remains critically important. On January 28, a USAID regional contracts officer sent a notice to implementing partners requesting them to “pause all expenditures … that both support family planning and that also benefit the government of Burkina Faso at any level (local, provincial and national).” To date, the State Department has not made a formal designation of a coup d’etat in Burkina Faso.

When coup determinations are made, the USAID Office of Population and Reproductive Health, country missions and lawyers can either seek to shift FP/RH activities involving the sanctioned government to the private sector or invoke an exception that is available under the law for “life-saving” activities, a designation which can typically be applied to FP/RH service delivery and contraceptive procurement and distribution, but not for other important programmatic activities.

Burkina Faso may soon join the list of African countries in which family planning programs have been disrupted by coup determinations recently, specifically in Mali (May 2021) and Guinea (September 2021). Assistance to FP/RH activities in Mali through the government has been restructured and transferred to the private sector, while sorting out how to reorient the program in Guinea remains in progress.

Forcing USAID to scramble to restructure FP/RH assistance to governments and channel it through the private sector — or invoking the “life-saving” exception — is time-consuming, expensive and not a cost-effective use of taxpayer dollars. Since there is no programmatic rationale for objecting to the technical language change — included in both the House and Senate versions of the bill and requested by the president in the FY 2022 budget appendix — one can only conclude that Republican opposition is either rooted in a desire to single out and punish the bilateral FP/RH program or a mindless demand to not deviate even a tiny bit from the legislative status quo. The thousands of people in those countries who would benefit from expanding the notwithstanding authority will continue to bear the consequences.

Fate of Other Pro-SRHR Provisions

The House-passed and Senate draft bills contained a multitude of extremely progressive pro-SRHR provisions in either the bill themselves or accompanying report language, all of which were jettisoned at some point in the discussion over the omnibus and sacrificed on the altar of the status quo, including:

HIV/AIDS Working Capital Fund

Current law only allows “child survival, malaria, tuberculosis and emerging infectious disease” programs to use the HIV/AIDS Working Capital Fund to procure and distribute pharmaceutical commodities for use in U.S. government-funded programs “to the same extent as HIV/AIDS pharmaceuticals and other products.” A simple wording change — adding “other global health” — to the existing statute had been requested in the appendix to the president’s FY 2022 budget request and inserted in both the House-passed bill and the Senate version. This would have broadened the fund’s eligibility to allow USAID the option of procuring contraceptive commodities using this mechanism if it chose and eliminated another instance in which FP/RH programs are subjected to discriminatory treatment in appropriations legislation without legitimate programmatic justification. The omnibus text reverts to current law.

Peace Corps

The House-passed bill also deleted the prohibition on the use of Peace Corps funds to pay for abortion services for its volunteers, except in the cases of life endangerment, rape or incest. Since 1979, the Peace Corps has been prohibited from providing coverage for abortion services in its health care program, with no exception. Peace Corps volunteers only began receiving coverage for abortion services in cases of the three exceptions in FY 2015 when language referencing the Federal Employees Health Benefit Program was added to that year’s appropriations bill after a campaign for equal treatment was mounted. Bringing its health coverage in line with that of other employees or groups covered by the federal government was an important and meaningful change for the Peace Corps. The omnibus restores the restriction in current law, including the Hyde amendment exceptions for volunteers.

Full and accurate information on condoms and contraceptives

A statutory requirement directing that complete and medically accurate information on the use of condoms be provided in U.S.-funded programs was first included in appropriations legislation in FY 2004, the year after the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) was first authorized, in response to reports that some PEPFAR grantees were disseminating misinformation on the effectiveness of condoms in the prevention of HIV transmission. The House-passed bill adds “modern contraceptives” to the existing requirement to ensure that information on family planning methods and services is also medically accurate, in order to guarantee that women who benefit from U.S.-funded programs are fully informed about all their options for preventing unintended pregnancies. The omnibus retains the existing requirement only as it applies to condom information.

Helms amendment

The House-passed bill’s most dramatic departure from prior-year legislation was dropping all references to the 1973 Helms amendment that restricts use of foreign assistance funds to pay for the performance of abortion “as method of family planning or to motivate any person to practice abortions.” In most years, foreign aid appropriations bills, beginning in FY 1980, reiterated and reinforced the Helms amendment, a section of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, the permanent authorizing statute governing U.S. overseas aid programs. The Senate bill did not follow suit. Not surprisingly, the omnibus reinserts the Helms amendment language in both the global health section of the bilateral economic assistance title and the general provisions title of the bill in the same way as it appears in last year’s omnibus spending bill and for many preceding years.

In contrast, both the House and Senate versions of the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education bill removed the Hyde amendment, an annual appropriations “rider” that has barred states from using federal Medicaid funds to provide abortion, except in cases of life endangerment, rape or incest, since 1976. As expected, the removal of the Hyde amendment became a major target of the Republican leadership’s ire and was reinserted in the final FY 2022 spending package.

Report language

Not satisfied with maintaining a rigid consistency in the text of the bill, Republicans insisted on excluding pro-SRHR provisions inserted by House Subcommittee Chair Barbara Lee and Democratic appropriators and staff in the House report. Because of the unique circumstances of this year’s negotiations over the final FY 2022 spending bill — House-passed bill being conferenced with a draft Senate Democratic subcommittee “chairman’s mark” — the joint explanatory statement incorporated the House report language verbatim (by reference), except where explicitly excluded. Unfortunately, many of the explicit exclusions related to reproductive health, family planning and contraception.

As specified in the joint explanatory statement accompanying the omnibus, “The agreement maintains prior year funding levels and policy related to family planning/reproductive health. The agreement does not endorse directives under certain House report headings: Reproductive health and voluntary family planning; Research, regarding contraception; and Women’s reproductive healthcare in El Salvador.” Republican opponents are nothing if not thorough in their pursuit of removal of any piece of legislative language that might in any way endorse an enhancement of SRHR.

What’s Next

With the completion of the FY 2022 appropriations process, the funding cycle begins anew as we look ahead to FY 2023. However, the sad fact is that FY 2022 was the fiscal year to finally enact a permanent GGR repeal into law and Congress failed.

Despite this disappointment, advocates will continue the fight for SRHR knowing strong champions in Congress will back us up. As the women leaders of the House Pro-Choice Caucus made clear in a firm and combative statement in the aftermath of the adoption of the omnibus, they “will continue to partner with, and fight alongside, our friends in the reproductive health, rights and justice movements” and are “more committed than ever before to continuing our fight to ensure everyone has the freedom to make decisions about their own health, bodies and lives.”

Awaiting completion of the omnibus, the release of the president’s FY 2023 budget request is now expected to arrive on Capitol Hill sometime before the end of March. It’s a new opportunity for the White House to visibly showcase its support for international FP/RH, as well as broader foreign assistance. Doing so would kick off the FY 2023 process with renewed energy and optimism, which will be much needed in an election year that will reduce the amount of time members will be in Washington to work on a spending bill for the new fiscal year that begins on October 1.

Stay tuned for an analysis of President Biden’s second federal budget request, coming soon.

We are fighting back against the onslaught of harmful policies that discard reproductive rights.

Stay informed about the issues impacting sexual and reproductive health and rights.